This guest blog post was authored by research advisor Stephanie Tepperberg.

In the Netherlands, approximately 50 percent of primary school children ride their bikes to school, and even more ride their bikes to secondary school.1 What’s more, Dutch cyclists are about 30 times less likely to get injured cycling than Americans.2 This begs the question: how do they achieve such high levels of ridership and low rates of injury? The literature has touted numerous Dutch practices as contributors to high levels of cycling and cycling safety. Specifically, bicycle-friendly infrastructure in the Netherlands allows children to safely travel to school; close proximity of schools to homes facilitates greater active transport; and early bicycle and pedestrian safety education leads to greater awareness and safety for all road users.3

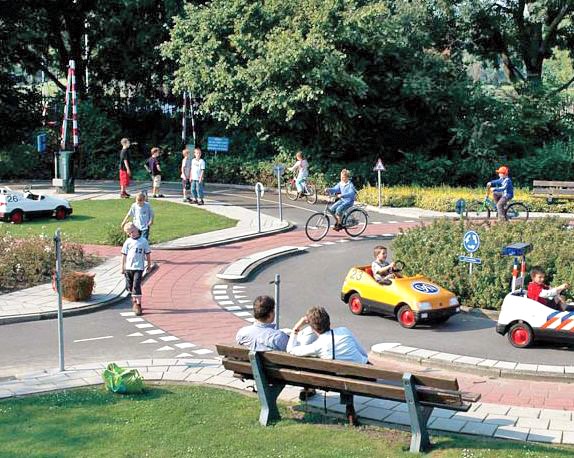

For more than 60 years, the City of Utrecht, Netherlands has operated a traffic garden (see picture below) - a simulated road network where children learn how to navigate city streets and become responsible and safe users of the road.4,5 Originally started in response to concerns about children’s traffic safety after a boom in urban car ownership and use post-World War II, today, children take regular field trips to the traffic garden, as early as elementary school, to practice safe biking, pedestrian, and driving skills.6

Example of a traffic garden in Utrecht, Netherlands.8

The layout of the traffic garden is that of a mini-street network, with simulated roads, traffic circles, crosswalks, signs, and signals. When children first arrive at the traffic garden, they receive a short safety lesson in the classroom and then students are split up into three groups – drivers of small cars, cyclists, and pedestrians – to practice safe traffic behavior. If during practice a child fails to operate their vehicle or bicycle safely, they may lose their privileges temporarily, similar to in real life.7

In addition to traffic gardens, primary schools in the Netherlands provide substantial education related to bicycling on city streets from an early age. By the age of 10, primary school students are taught safe walking and biking strategies, traffic regulations, and defensive active transportation skills through written and practical learning activities.9 In order to ensure understanding, prior to entering secondary school, Dutch students are required to take both a theoretical and practical bicycle exam in order to earn a bicycle diploma.10 Teaching bicycle safety and the rules of the road early on helps Dutch students commute responsibly and safely via bike throughout primary and secondary school, and helps society understand the rights of the people bicycling on the road.

Safe Routes to School includes education as one of the six E’s in its comprehensive approach to increasing bicycling and walking to school. The early educational practices and norms highlighted from the Netherlands that contribute to greater student cycling rates to school and safety on the road are innovative ideas that Safe Routes to School practitioners should consider and adapt. With the use of chalk or temporary road paint, traffic gardens can be created in empty parking lots, alleys, or asphalt playgrounds, such is suggested by Dutchess County in New York during bike rodeos.11 Early bicycle education in elementary and middle schools can also be encouraged through extracurricular activities, incorporation into drivers’ education in high school, or during walking school bus trips to ensure that our young people know not only how to safely bicycle themselves, but also how to safely drive and consider bicyclists on the roads.

[1] Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat. "Cycling in the Netherlands." 2009. http://www.fietsberaad.nl/library/repository/bestanden/CyclingintheNeth….

[2] Pucher, John, and Lewis Dijkstra. "Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling to Improve Public Health: Lessons From The Netherlands and Germany."American Journal of Public Health93, no. 9 (September 2003): 1509-516. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509.

[3] Pucher, John, and Lewis Dijkstra. "Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling to Improve Public Health: Lessons From The Netherlands and Germany."American Journal of Public Health93, no. 9 (September 2003): 1509-516. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509.

[4] "Cityplaydesign." 2016. http://www.cityplaydesign.com/blank.

[5] "Utrecht's 'traffic garden' helps kids become responsible road users." BikePortland.org. August 20, 2009. Accessed February 01, 2017. https://bikeportland.org/2009/08/20/utrechts-traffic-garden-helps-kids-….

[6] van der Zee, Renate. "How Amsterdam became the bicycle capital of the world." May 5, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/05/amsterdam-bicycle-capita….

[7] "Cityplaydesign." 2016. http://www.cityplaydesign.com/blank.

[8] Kiker, Elizabeth M. "Traffic Gardens Galore." January 5, 2015. https://www.cascade.org/blog/2015/01/traffic-gardens-galore.

[9] Pucher, John, and Lewis Dijkstra. "Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling to Improve Public Health: Lessons From The Netherlands and Germany."American Journal of Public Health93, no. 9 (September 2003): 1509-516. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509.

[10] 21, 2013, September. "Could you pass a Dutch bicycling exam? - The Boston Globe." BostonGlobe.com. September 21, 2013. Accessed February 01, 2017. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2013/09/21/how-much-you-know-about-bike-saf….

[11] Dutchess County Traffic Safety Board. "Organizing a Bicycle Safety Rodeo ." November 2003. http://www.co.dutchess.ny.us/countygov/departments/trafficsafety/bicycl….